-Adrianna

My thoughts after reading “Everything is a Metaphor: Care as Praxis”…

Not sure if it’s because of the plant references, but I really enjoyed reading this. The forest metaphor and poem really got me thinking. It teaches us that to care is to evolve. When you care for others and yourself, you grow (from plant to forest). A forest is an abundance of life and its ecosystem is a community. This makes me think back to the Tsing reading we did on the first day about mushrooms and communities.

Two lines that stood out:

“Ultimately, he identified that part of his challenge in defining care stemmed from the fact that it looks different for everyone and manifests differently in different contexts.”

-Perhaps today is a good time to re-define care as a collective. How do we all re-define care? As this reading suggests, care varies from person to person. But as the semester progressed we’ve all been constantly defining and redefining power, precarity and care. Since the first day of class and up until last week, I’ve been thinking about care as “self-care”. But now that I’m working on my final projects (they’re about community and feminism) I find myself rethinking my definition of care. Now, I see care as “community care”. Perhaps the best way I embody it is through respecting others and practicing active listening .

“Care requires both time and attention. Time. And. Attention.”

-This is the million dollar question I’ve had all semester. I’d love to practice this type of pedagogy. My question is How? What if we as students + adjuncts don’t have the time? How can we properly care for other AND ourselves at the same time? I still feel like this seems hard to achieve due to our precarious position in the institution.

Care and Institutions — from Sean

I am not a fan of the forest metaphor. Partially because I’ve spent time in forests and did not enjoy it at all and partially because it drifts too much towards the whole “noble savage” thing for my tastes.

I’m not saying that the piece is bad or wrong. It makes many valid points, I just don’t care for the metaphor.

It has been my experience that you cannot look for any care from the institution. A few stories:

Eight or nine years ago, one of our adjuncts was physically attacked by a former student. The student had been suspended for academic reasons and blamed my colleague. So, the student assaulted him at the end of a class.

What did the administration do? Not a single (expletive) thing. They didn’t even offer my colleague counseling until our area coordinator made so much noise they couldn;t ignore him.

The next term, my colleague was teaching three sections of public speaking. Guess who was in one of them? Yes, the student who attacked him. My colleague walked out and refused to teach the class.

Added bonus: this happened before the online sexual harassment and workplace violence prevention training started, so we were visited by human resources about these topics at the next department meeting. We asked if the college would back us up if a student attacked us and we defended ourselves.

They did not give a straight answer, which, to be clear, means “no”.

______________________

Then in 2018, several of our instructors were having issues with students: one was being stalked, another was threatened, a third was being harassed by students, so our department chair organized a panel with four people from counseling and public safety. Let me boil down their commentary.

Person one (public safety): Immediately get security involved. Document everything. File a report the day it happens.

Person two (not sure where this person was from but they had the flat, emotionless affect of a serial killer): Whatever you do, do not get security involved.

Person three: You need to get in touch with your department chair if this is an issue.*

Person four (this is paraphrasing, but it’s what he meant): Students are acting up because none of you can teach.

So, we don’t have anything that resembles coherence at the administration level for safety concerns. We aren’t the only campus like this. I’ve heard tales from a few other campuses.

*At one point, the official policy was that we couldn;t contact campus security if an incident took place until we had cleared it with our department chair. My chair announced at a meeting that he gave all of us permission to do what we needed to.

Yes, these are extreme examples and not everyday occurrences by any means, but I’ve also seen the administration screw with faculty and staff who have lost a loved one or who are on leave.

My point is that the administration will do nothing, unless you find someone higher up in the power structure to advocate for you. You need to establish relationships with colleagues (as difficult as that can be sometimes) so that when things go wrong you have a safe place to turn for advice and comfort.

I do not know how we can hold institutions accountable for their (lack of) action. In many ways, I’m concerned for my own future at LaGuardia because my current area coordinator is stepping down at the end of June, and the new coordinator is… not tech friendly**, and therefore, does not see much value in what I do.

I’m just tambling now, so I’m going to stop, and I apologize because I feel that this might not be exactly on topic.

**And in the year 2023, not being tech friendly shouldn’t fly, but this is one of those “I’ve been teaching this way since the Pleistocene” people. It’s frustrating.

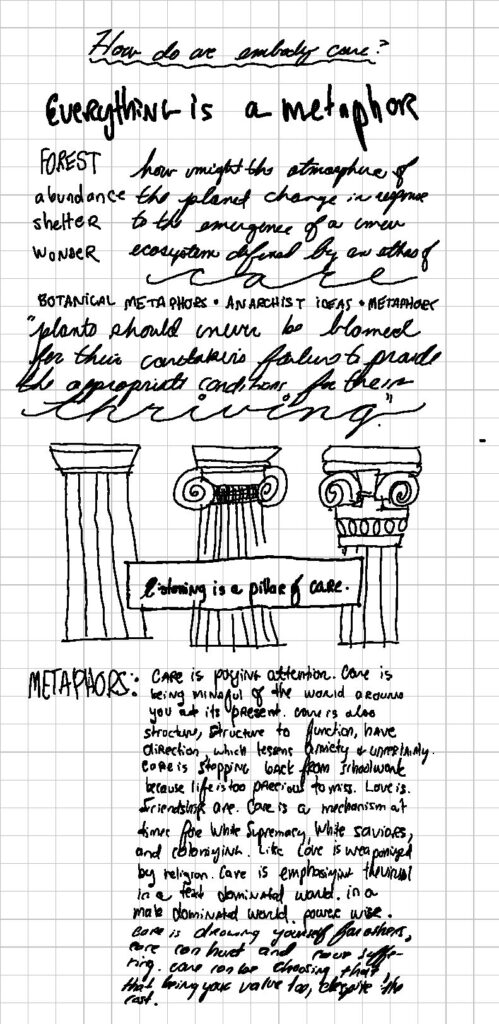

Care as a metaphor: visual

brie scolaro

Week 12

by Jen

Thanks so much for including a reading from Knowledge Justice! This is such a good and important book for my own field of work; I guess, to step back for a moment from the substance of the chapter we read, there’s a lot that we could talk about simply related to the way this book is a manifestation of care: the fact that it exists as a project (a brilliantly POC-led writing project in a field flooded with scholarship that is really dominated by whiteness) attests to the care and dedication of its editors; the work inside it comes not only from the care of chapter authors but also from an editorial process that I know was filled with a lot of care; the fact that it’s open access also feels to me like a way we can show care for how knowledge exists and is shared.

Anyway.

There were some questions that came to me at the intersection of Cong-Huyen and Patel’s chapter and the Project Nia video; it was really interesting for me to reflect on whether the substance of the video, which felt like it was focused on bringing individuals into spaces of accountability and care, could also speak to Cong-Huyen and Patel’s writing, which calls for institutions/disciplines to be accountable. One of the themes that came up for me throughout the video was the need to make sure that folks going through accountability processes have resources to care for themselves in the meantime: transportation, shelter, food, personal relationships. If we transfer this need for accountability processes to our professions and institutions, what are the resources that our professions and institutions need in order to care for themselves / feel supported while working towards accountability? I was reflecting on our conversations last class about dependencies, and my own fixation in that conversation on very material dependencies (lightbulbs, bathrooms). My profession, like many others, badly needs accountability for how its lack of diversity impacts individuals in the field, how are we supposed to work together as a profession towards being accountable and caring when we don’t have enough lightbulbs to light up the library? How are we expected to be thoughtful and reflective about systems of power and oppression in our field when we have to spend so much time fixing staplers?

It’s embarrassing that white supremacy can be perpetuated by a lack of basic resources; we should be able to focus on the big issues even while these small things need to be tended to.

But also: is this how administrators make sure that systems of power don’t change? (I mean…I didn’t actually need to put a question mark at the end of that sentence…) We are forced to spend all our time filling out forms for photocopier maintenance, and so we can’t engage with each other in meaningful conversations about what could improve the real substance of our institutions.

Reflecting then on how we could embody care, even in spaces where we aren’t being given the resources we need to attend to our basic needs: perhaps this looks like

- sitting with someone while they fix a stapler, and having a real conversation while sharing the frustration of unmet resources.

- sharing the resources we’ve scraped together with each other: in the context of Cong-Huyen and Patel’s piece, I’m thinking specifically of how myself and colleagues who have shared frustrations about dealing with immigration issues while working for employers who don’t understand that bureaucracy, have created networks and relationships to share information with each other to help navigate those isolating (and terrifying) processes.

This might also look like: building relationships to share information about health care providers who actually accept the (often inadequate) healthcare provided by the employer. Or, sharing knowledge about personnel processes and experiences about navigating tenure and promotion processes. - prioritizing conversations about accountability, systemic injustice, and institutional care, when we can, even if / while acknowledging that we aren’t coming to the space individually with adequate resources to feel prepared/cared for.

- recognizing that other people will experience care differently than we each do, and finding ways to attune ourselves to that

Distant Reading for Care Key Words.

Tuka Al-Sahlani

So, I decided to “play” with other ways to read and write my post this week. I was very interested in the Praxis Program Charter. I decided to see if the language change pre, within, and post pandemic. Below are links of the word clouds:

18-19 Cohort

https://voyant-tools.org/?corpus=321b07bf4fb4ff5deaf27d6d4b7f03c2&view=Cirrus

20-21 ( COVID is explicitly stated in the preamble)

https://voyant-tools.org/?corpus=963b5105cf810bbdf653994f7e751b6d&view=Cirrus

20-23 ( Post? Covid)

https://voyant-tools.org/?corpus=02894679288426ae6dea9a916525a654&view=Cirrus

Time is highlighted in the 20-21 charter. It is the charter that has time repeated 11 times. In the 18-19 time is repeated twice and in 20-23 time is repeated 20-23. Dutring the pandemic time was finite and a commodity. Many of us practiced care for ourselves and for others by considering time a space of care. I am intrigued and concerened: are we going to forget to care and value our time as we return to “normal”?

is institutionalized carework a trap?

by d

some thoughts i’m still developing…

this line from Risam’s work is sticking with me: “participating in diversity work is a trap into which those whose work is guided by an ethical commitment to communities underrepresented in academia and those who belong to these communities risk falling.” reading this essay reminded me of the many instances where i’ve been asked to take on additional labor (emotional labor/knowledge production/interpretation for my Spanish speakers) without any compensation, and how i was convinced that this was “for the community.” but that labor was swallowed up by the institution, and in so many ways, de-prioritized. for example, i think of being promoted in a previous workplace, and no longer having capacity to interpret during family-teacher conferences (a service i provided to mainly Latine immigrant mothers)…all of a sudden there was room in the budget to hire interpreters (i no longer offer translation/interpretation services for free). i’m thinking about the trickle effect. how the devaluation of my labor in so many ways was a deprioritization/dehumanization of specific groups of people.

i’m thinking also about performative diversity — how often i’ve witnessed incredible adjuncts who are hired … i’m guessing because it’s good marketing, and not necessarily because their work is valued within an institution. it’s too many times that these individuals’ labor has been treated as disposable. i’m thinking about labor and time extraction within the academy, and how it directly influences the lives of BIPOC who enter the academy with the hopes of making a difference. i’m thinking about how carework is invisibilized through algorithms in digital spaces.

tbh — this week’s readings felt…exhausting. because i feel caught in this trap. and i’m not sure exactly what the way out is…

Care Day 3

-Adrianna

Fragmented thoughts on the Roopika Risam article:

*This piece reminded me of issues posted by Lorgia García Peña and Moya Bailey

*”The neoliberal university expects representation but resists transformation” –> This quote is everything! Our semester in a nutshell.

*Thinking about care as gendered and feminized: These women feel strongly about their work. Using them for “housekeeping” to counteract and prevent backlashes is humiliating and almost victimizing them all over again. Who “cares” for them? What are alternatives that institutions use? Are there any?

*As you all know I’m in my first year, but so far I’ve had a positive experience with CUNY. I think that the best tools this institution has given me are the curriculum and freedom of craft. Still, I’d like to know what are other tools that CUNY has to counteract the issues presented by Risam? In that sense, how does CUNY differ from other institutions?

Some thoughts from Sean

Some thoughts after doing the readings:

The Bisam piece reminded me of my first trip to grad school, when I was getting my degree in Teaching English a Second Language. At the time, this degree was awarded from the Division of English as an International Language, and it attracted a lot of Christian missionaries.

I am gay.

This was not always the best environment. The professors were fine, as were many of my fellow grad students, but the ones that weren’t REALLY weren’t.

I got the conversations that pretty much every queer person in the 90’s (and earlier) got – you know– “When did you decide to be gay?” “Have you tried prayer?” “I’m fine with gay people, as long as you aren’t TOO gay.” That sort of thing.

Here’s the issue: I could have filed complaints. I’m pretty sure that the university had an anti-LGBT policy, but the sheer volume of drama that would have caused would not have been worth it.

So, I minimized my contact with those particular grad students and became monumentally unpleasant when they said something out of line. The peak moment of this was when I was teaching English to incoming international MBA students and, at a weekly meeting with all the grad students teaching there, one of the Christians went off on a tangent, discussing his own personal theories of why people are queer.

Nowadays, I would have said, “Sir, this is a Wendy’s.”

However, back then… I said something like “What the (expletive) does that (expletive) have to with any-(expletive)-thing?”

Afterwards, our supervisor pulled me aside, and said that while she understood my anger, I was out of line. She went silent when I asked why she didn’t shut the guy down.

I never got a response.

In other words, you can’t really rely on power structures to help you, and, honestly, fighting is exhausting, so people normally end up picking their fights.

_____

The Praxis Program Charters

I thought these were by and large interesting and there is a lot here to compliment. The idea of setting up an environment that is open and that accepts failure is important and useful. Keeping everyone informed of each other’s progress (or lack thereof) is also an excellent idea.

A lot of this boils down to having lines of communication, which is the idea and it’s great when it can be pulled off.

However, the level of socializing within the cohorts got to me after a while. I guess this is because I don’t like most of the people I work with. This isn’t to say I hate them… I’m just not friends with most of them. Having a weekly lunch or drinks with them sounds painful, and I say this as an extrovert.

I spend my workday with them, but once I’m done, I want to be literally anywhere else. I like to keep my social life and my work life separate.

But, like I said, overall, I genuinely support most of what was said in these.

Week 11

This week’s had me thinking a lot about the nature of scrappy and DIY work, and when it becomes too much.

I really appreciated Cecile and Merriam’s reflections on how, at Bard College, they lacked a robust budget to build up their program’s technological infrastructure; in response, they relied on free tools and also built networks with colleagues who could loan materials. I think this is a terrific idea for many reasons: it builds relationships and avoids siloed programs; it shares resources in what is likely an environmentally friendly way; it sets up students to be resourceful in working on DH projects in similarly under-resourced settings outside the institution. (One of my own most valuable experiences in graduate school for library science involved a web designer teacher letting us know that we were free to use all the subscription software available in our department’s computer lab, but that she planned to teach us how to do all our assignments using the software that is available on a Windows PC — because she knew many of us would work in spaces where that was our only option. I cannot stress how useful that was to me; I can hack a wild amount of web design in Word and Paint.)

At the same time, I think we run a risk when we encourage construction of this kind of scrappy infrastructure: Risam reminds us of the emotional labor of digital carework for diversity, and this builds upon the emotional labor required to construct DIY DH spaces: the labor of relationship building, of maintaining equipment lending programs, of sustaining projects built with free technology that may not have any enduring investment supporting it.

It’s fun and exciting to pull things together on a shoestring budget, often in the face of seemingly impossible odds. But, does it really model care to suggest that this is the way to go? What is the boundary that we need to model for saying: if there’s no infrastructural support from the institution, the personal/emotional/relational cost is too high. I’m not really sure; it might differ in every institution, every project, and for every team and individual. But: how do we teach that this boundary can and should exist, if we want to cultivate DH workers who perform care for themselves, their work, and their communities?

Week #10: Care-full Teaching

by Anthony W.

Pedagogies of care are a driving concept behind why I pursued an M.A. in DH and persisted onward to the Ph.D. in Urban Education. However, I didn’t come at it from the angle of being mindful of self-care (I mean, I’m pursuing a Ph.D., which is traditionally very anti-self-care lol) but rather from how to enact care through the projects and work we do together. I wrote about care a bit in my master’s thesis, the ways it’s expressed through educational decisions, and how transforming projects to be culturally conscious, exploratory, and positioning students as creators (for example, I allowed my composition students to cite themselves in their final research paper after they had produced digital artifacts) can be seen as a form of care-full learning. I think Jen’s mind map is a good representation of some of the ways I see care in learning spaces as well.

As you all appear to, I also feel strongly about the idea of self-care, considering how demanding working in academia and pursuing a doctoral degree can be. There are a lot of associated expectations/stigmas surrounding pursuing a graduate degree, such as sacrificing your social life, that I simply don’t believe are practical for me (or anyone) to have to accept in the pursuit of knowledge and understanding. In many ways, the training processes we go through in our 5+ years as doctoral students prevent us from enacting proper care toward ourselves for prolonged periods. I recall once reading a tweet from someone who had recently finished a Ph.D., and it regarded their excitement when they realized they enjoyed and were good at cooking, followed by an explanation of how they assumed they weren’t a good cook and were constantly ordering in throughout their graduate studies due to simply not having time to practice their cooking skills and not needing to since food can easily be brought to your door now. This is a random example, but it did cause me to reflect and look at how often I prepared home-cooked meals during my M.A. program versus my Ph.D. program, and I agree with the author of the tweet; it is quite a staggering difference. All of this to say, care is a radical choice that should be considered throughout the entire institution, not just on small-scale teaching moves, or to be [just] practiced alone, or by bringing puppies onto campus to alleviate stressed students during finals and dubbing it care/wellness, but by restructuring systems to consider basic human needs and how to satisfy those first.