by Jen

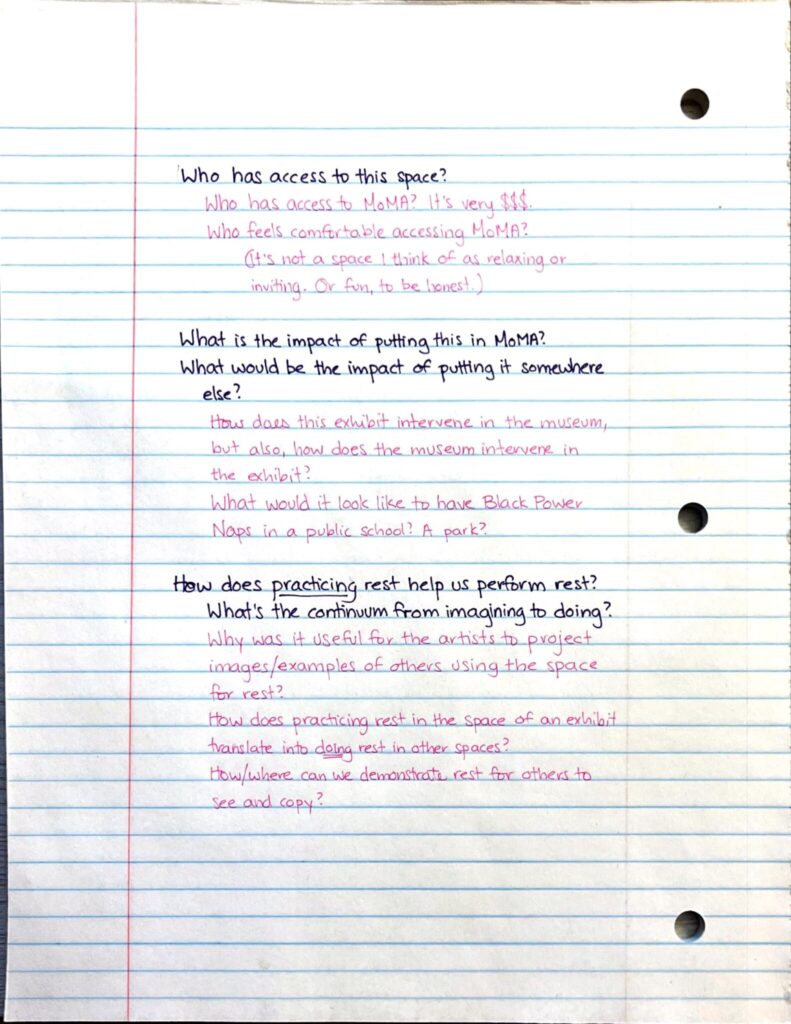

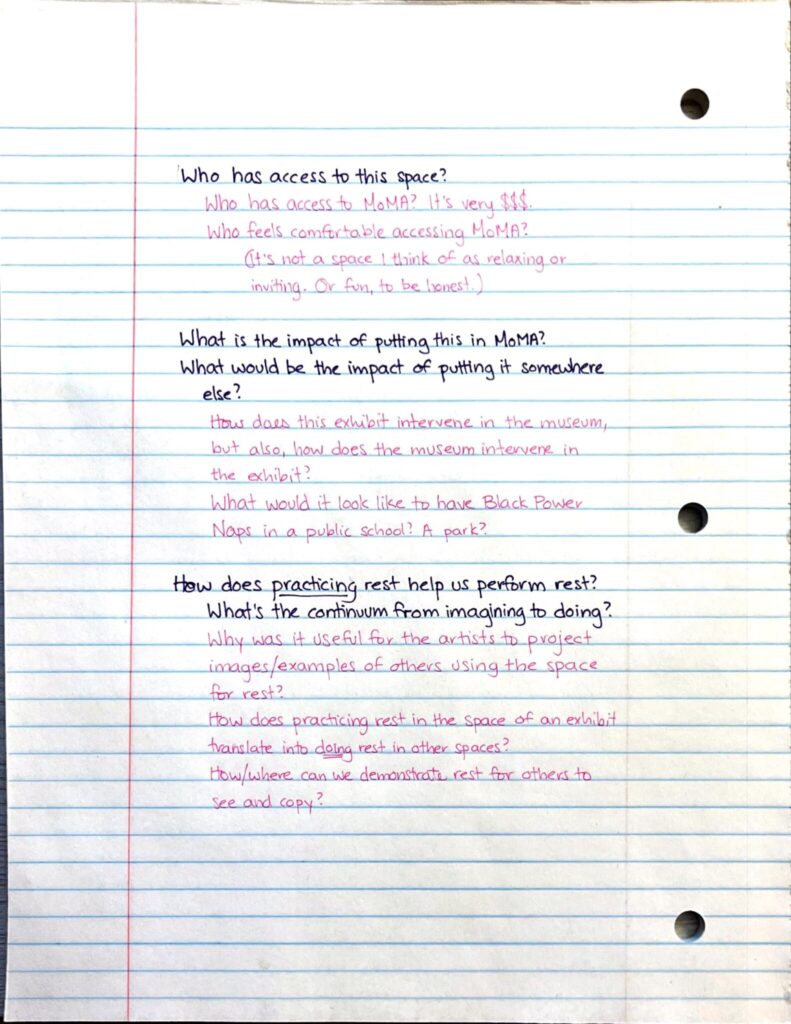

I sat down to write out some of the questions I was thinking about while in the exhibition yesterday: questions about exhibition space, about rest, about museums. I am still mulling a lot of these over!

by Jen

I sat down to write out some of the questions I was thinking about while in the exhibition yesterday: questions about exhibition space, about rest, about museums. I am still mulling a lot of these over!

by Jen

Thanks so much for including a reading from Knowledge Justice! This is such a good and important book for my own field of work; I guess, to step back for a moment from the substance of the chapter we read, there’s a lot that we could talk about simply related to the way this book is a manifestation of care: the fact that it exists as a project (a brilliantly POC-led writing project in a field flooded with scholarship that is really dominated by whiteness) attests to the care and dedication of its editors; the work inside it comes not only from the care of chapter authors but also from an editorial process that I know was filled with a lot of care; the fact that it’s open access also feels to me like a way we can show care for how knowledge exists and is shared.

Anyway.

There were some questions that came to me at the intersection of Cong-Huyen and Patel’s chapter and the Project Nia video; it was really interesting for me to reflect on whether the substance of the video, which felt like it was focused on bringing individuals into spaces of accountability and care, could also speak to Cong-Huyen and Patel’s writing, which calls for institutions/disciplines to be accountable. One of the themes that came up for me throughout the video was the need to make sure that folks going through accountability processes have resources to care for themselves in the meantime: transportation, shelter, food, personal relationships. If we transfer this need for accountability processes to our professions and institutions, what are the resources that our professions and institutions need in order to care for themselves / feel supported while working towards accountability? I was reflecting on our conversations last class about dependencies, and my own fixation in that conversation on very material dependencies (lightbulbs, bathrooms). My profession, like many others, badly needs accountability for how its lack of diversity impacts individuals in the field, how are we supposed to work together as a profession towards being accountable and caring when we don’t have enough lightbulbs to light up the library? How are we expected to be thoughtful and reflective about systems of power and oppression in our field when we have to spend so much time fixing staplers?

It’s embarrassing that white supremacy can be perpetuated by a lack of basic resources; we should be able to focus on the big issues even while these small things need to be tended to.

But also: is this how administrators make sure that systems of power don’t change? (I mean…I didn’t actually need to put a question mark at the end of that sentence…) We are forced to spend all our time filling out forms for photocopier maintenance, and so we can’t engage with each other in meaningful conversations about what could improve the real substance of our institutions.

Reflecting then on how we could embody care, even in spaces where we aren’t being given the resources we need to attend to our basic needs: perhaps this looks like

This week’s had me thinking a lot about the nature of scrappy and DIY work, and when it becomes too much.

I really appreciated Cecile and Merriam’s reflections on how, at Bard College, they lacked a robust budget to build up their program’s technological infrastructure; in response, they relied on free tools and also built networks with colleagues who could loan materials. I think this is a terrific idea for many reasons: it builds relationships and avoids siloed programs; it shares resources in what is likely an environmentally friendly way; it sets up students to be resourceful in working on DH projects in similarly under-resourced settings outside the institution. (One of my own most valuable experiences in graduate school for library science involved a web designer teacher letting us know that we were free to use all the subscription software available in our department’s computer lab, but that she planned to teach us how to do all our assignments using the software that is available on a Windows PC — because she knew many of us would work in spaces where that was our only option. I cannot stress how useful that was to me; I can hack a wild amount of web design in Word and Paint.)

At the same time, I think we run a risk when we encourage construction of this kind of scrappy infrastructure: Risam reminds us of the emotional labor of digital carework for diversity, and this builds upon the emotional labor required to construct DIY DH spaces: the labor of relationship building, of maintaining equipment lending programs, of sustaining projects built with free technology that may not have any enduring investment supporting it.

It’s fun and exciting to pull things together on a shoestring budget, often in the face of seemingly impossible odds. But, does it really model care to suggest that this is the way to go? What is the boundary that we need to model for saying: if there’s no infrastructural support from the institution, the personal/emotional/relational cost is too high. I’m not really sure; it might differ in every institution, every project, and for every team and individual. But: how do we teach that this boundary can and should exist, if we want to cultivate DH workers who perform care for themselves, their work, and their communities?

— by Jen

For this week’s reflection, I made a mind map of different ideas of “care” that I saw in My Pandemic and in Reclaiming our Time. This mind map isn’t super scientific; ultimately, I chose first-level categories because I wanted them to stand out as more important; I added items attached to these when I thought that they nested well within categories…but we could move things around by category, or move things up within category hierarchies, in endless iterations of this.

While the image below is static (and tiny!), you should be able to navigate around the mind map at this link.

Because I spend so much time thinking about classification and categorization, I enjoyed a chance to reflect on how tools like mind maps result in classifications and hierarchies, even if our intention isn’t to create hierarchy.

— by Jen

I really appreciated Connection Established because of the way it clearly illustrates the complexity of caring for others while needing care yourself. I also appreciated that the things in this story that felt like the most important instances of care are actually (feel free to argue with me on this…) some of the simplest: stopping to talk with someone; finding moments for personal connections; recognizing that prioritizing someone else’s needs doesn’t necessarily mean you’re deprioritizing your own (care doesn’t have to be a zero-sum activity).

Translating some of those concepts over to the introduction of Design Justice, I can see this kind of care in the design firm And Also Too, which believes that “absolutely anyone can participate meaningfully in design.” I’m interested, then, in what the mechanisms are to facilitate listening / making space for anyone to participate, when the typical methods for design work haven’t made space for everyone.

Empathy is an ideology was a really interesting read; I appreciate the way that Jade Davis articulates the weaponization of empathy. And, I agree with their statement that “empathy does not lead to radical action.” I suppose that I want to push back on that a little: empathy doesn’t necessarily lead to radical action, but it could. And, a lack of empathy also doesn’t lead to radical action…but, it could. I suppose the problem comes in assuming that empathy is enough; that empathy is care; that empathy is an end point rather than part of the process towards action and change. While reading this piece I was thinking a lot about Gloria Ladson-Billings’ writing on culturally relevant pedagogy (summarized fairly well here; also in this fairly short interview from 2022). The cultural competence and critical consciousness elements of her work rest on empathy, but I think she’s articulating that we need cultural competence (empathy) as well as critical consciousness (which I read as action, rooted in empathy). So what I’m trying to say is: I can agree that empathy isn’t enough, but I’m not convinced that empathy in itself needs to be read as quite so negative is I thought Davis does.

— Jen

Thanks so much for this reading, Adrianna and Brie and Nelson! I really enjoyed spending time with it.

Bailey’s note that “graduate students are expected to enter the job market with at least one published peer-reviewed article” made me pause and think about an incident that happened to me when I finished my MLIS and started working as a librarian. I think that different students have different experiences at different institutions, but I had attended graduate school for library science at a very research-focused institution; I wasn’t really aware of that at the time (and honestly, I regret it a little). The need to publish peer-reviewed articles was drilled into us so heavily; I graduated in a panic about how I could start publishing.

I started replying to CFPs. Sure enough, I was invited to submit full articles — two peer-reviewed submissions, as well as two chapters for a non-peer-reviewed book. The immediate problem was that I no longer had any academic affiliations — I was running the library of a small research institute — and so I had no way to access the literature I needed to cite. My quick solution was to audit a university class so that, for one semester, I could access the university’s databases. I cannot believe that the “logical” solution was to add more to my plate, so that I could do the things I’d already committed to.

The longer-term problem, however, was that no one at my fancy graduate school had taught us, while instilling us with anxiety about publishing, that some publishing opportunities are not good. I’m still proud of one of the articles I wrote during that period; it was really positively shaped and supported by the editors and peer reviewers. However, a second article from that time is one that I’m generally embarrassed to mention; it became clear that the editor didn’t have peer reviewers available and just had her own graduate student review it (thanks to non-anonymized tracked changes). That student really couldn’t give any useful feedback. I wanted (and needed) peer review for that article; I didn’t really get it, and I think the final product is sub-par.

I had proposed a chapter for a trade publication on libraries, and the editor invited me to write two chapters instead of one. I wrote them; she replied that they weren’t at all what she wanted and asked me to re-write them, which I did. She then rejected them entirely. There was a really clear lack of communication about what she ultimately wanted, but also, I later realized that this editor had a reputation. She was notorious for flooding the market with sub-par “how to” guides for librarians; she was also notorious for issuing CFPs for books that ultimately didn’t get published. How many other people worked hard to produce content for her, for projects that didn’t materialize? And, do I actually trust that she didn’t take my (or others’) rejected content and use it in other ways? No one told us in graduate school that this could happen.

What I was thinking about while reading Bailey’s note on the heightened anxiety around urgency of peer-review publishing and similar tasks, is how this anxiety causes us to put ourselves in harmful situations. If I hadn’t had a clearer sense of myself and known that I was ultimately a decent writer, my early experiences with publishing in my field would’ve likely left me unwilling to try it again. There aren’t really support groups for scholars who have to deal with terrible editors.

As a possible prompt for thinking more about this in class, some of the things I think about a lot as someone who continues to write but is also in an editorial role:

Hi all! I thought some folks here might be interested in this call for submissions: https://thickpress.medium.com/an-encylopedia-of-radical-helping-call-for-writing-and-or-images-3c4578833390

Note that the initial submission deadline was in January, but that has now moved to April.

by Jen

My final project asks: is the work of indexing and coding a text for analysis a reductive act, or can it be an act of care?

I bring to this work a perspective of the type of indexing that is typically done in libraries. This tends to focus on what a text is about; sometimes it will focus on who a text is by. Both of these feel reductive to me because determining “aboutness” is always a struggle and always requires focusing on some aspects more than others; I believe that some types of “aboutness” are always overlooked. A focus on authorship of a text is problematic because it complies with capitalist notions of authorship that celebrate specific types of contributions and that codify authorship in order to preserve economic benefit.

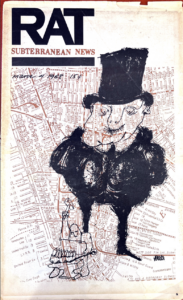

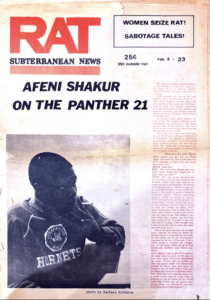

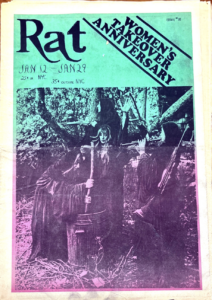

I have been working with a large number of newspapers from the radical Left in the 1960s and 1970s for my research. One of these, RAT Subterranean News, is notable because it changed halfway through its (3 year) lifespan after being taken over by a group of women. I have been curious about the different ways we can describe the impact these women had on the paper, but also, felt that a lens of subject analysis of the paper was not entirely helpful; when I took a quick pass at that work, I felt like I was boiling down the women’s contribution to “more articles about women,” but wondered how I could show that they are doing more than just elevating a content subject area that wasn’t there before.

I was deeply compelled by the recently released Letterpress Revolution, which explores the work being done specifically by anarchist newspapers. The author Kathy Ferguson created a set of types of work being done by different pieces of content in an anarchist newspaper: sharing news, creating public space, encouraging debate, etc. Her framework feels very applicable to me on a broader scale, outside anarchist publications.

Using that framework, I have started analyzing approximately 70 issues of RAT, from the first until (I think) the last. I am indexing each piece of content in the newspaper using Kathy Ferguson’s framework. My goal is to finish organize that analysis and then find a meaningful way to present that data that reveals some of the nuance that I think is missing in a subject-level analysis, and to depict what was being done by the women who took over RAT. How did their takeover of the newspaper transform that work that this publication was doing? Can we perhaps see that they imagined and realized greater possibilities for newspapers on the radical left? And ultimately, can this kind of analysis feel like it’s showing nuance and illuminating overlooked work, rather than feeling reductive?

The shape of my final project still feels a little murky. I’m not a whiz at data visualization, but will work on finding a way to share my findings visually. I imagine this would also be accompanied by a narrative providing context for my work and for the work of indexing this type of publication, as well as a textual interpretation of my results.

by Jen, in conversation with Magic Write

After working through this week’s readings I asked Magic Write, the AI inside Canva, to “discuss the hopes and harms of AI.” I’ve been curious about the existence of an AI inside Canva (a popular tool for generating social media content, marketing material, and even educational content); Canva isn’t the first place I’d look for an AI, but here we are. (The free version of Canva currently allows 25 Magic Write prompts; you need to pay to use the AI more.)

Magic Write’s response was:

AI has the potential to bring many benefits to our society, such as increased efficiency, improved accuracy, and the ability to tackle complex problems. AI can also save lives by improving medical diagnoses and drug discovery.

However, there are also concerns about the potential harms of AI, including job displacement, biases in decision-making, and the loss of privacy. AI could also be used for malicious purposes, such as cyber attacks or autonomous weapons.

Therefore, it is important to carefully consider the ethical and societal implications of AI and ensure that it is developed and used responsibly.

In a five-sentence response, I’m moderately impressed by the number of points the AI included. As a baseline, Magic Write is really good at a short answer question. However, it was interesting to me that there was no explicit mention of images created by AI, and so I followed up with, “What are the potential uses and abuses of image creation through AI?”

Magic Write’s response was:

The potential uses of AI-generated images include assisting in the creation of realistic and detailed graphics for various industries such as gaming, film, and advertising. However, the technology also raises concerns about the possibility of creating fake images for malicious purposes such as propaganda, phishing, and deepfakes. It is important to consider the ethical implications and potential misuse of AI-generated images.

One thing that was interesting to me in this week’s readings was a sense that the current wave of AI gives us something new. I don’t entirely disagree, but when Nitasha Tiku laments that “these systems produce images that can cause a range of harms, such as reinforcing racial and gender stereotypes or plagiarizing artists whose work was siphoned without their consent,” I couldn’t help but think about the ways that’s been happening for hundreds of years. AI certainly makes it faster, but anyone who has wanted to perpetuate harm in those ways has been doing it pretty successfully for a long time.

I was interested in thinking more about what, exactly, is new about AI; while reading about surveillance technology in proctoring programs and in grading, I agree that it’s all really sinister, but was curious about my inclination that this is just a new spin on an old trick. I asked Magic Write, “What are the uses of AI in surveillance of students through grading and proctoring?”

The response was:

The use of AI in surveillance of students through grading and proctoring can help to ensure academic integrity by detecting potential cheating and plagiarism. It can also provide a more objective and consistent evaluation of student work. However, it is important to consider privacy concerns and the potential for bias in the AI algorithms.

This resonated with me because of the statement that AI “can help to ensure academic integrity by detecting potential cheating and plagiarism.” That has literally always been the goal of any kind of proctoring and grading; aside from the fact of whether AI does it better than humans (which is probably debatable), I think we need to address the premise of this first: can any kind of grading and proctoring ensure academic integrity, or is academic integrity a biased and flawed notion in itself?

And, moving backwards, does AI increase the possibility of malicious image use, or have visual depictions always held the possibility of being used for malicious purposes?

Proceeding back to where I started, with the hopes and harms of AI, Magic Write’s response about the hopes of AI name a number of benefits that have value-laden assumptions built into them: efficiency, accuracy. I won’t argue that medical innovation is great, but we’ve always seen bias in the reality of medical innovation…for WHO?

While I’m open to being convinced otherwise, I don’t actually think that AI is creating more harms for us; AI is a mirror of the world we have already created (and fed into it), and I think it is just magnifying existing harms while reflecting them back onto us. Instead of being afraid of this, should we be grateful for the clear evidence of where things have gone wrong, and use this reflection that AI creates as a way to plan out where the work needs to be done?

by Jen

The manifesto from Precarity Lab and the article by Boyles et al provided an interesting contrast in looking at the human precarity of DH. Boyles et al focus on the academy, looking at the challenges faced by DH laborers; in addition to asking for better labor conditions, I felt that they were also asking for recognition of the work itself as labor: “Consider the graduate student encouraged to situate herself within digital humanities by completing digital projects in addition to a dissertation” (emphasis mine, page 694). There is an inference that these challenges arise because this work is new to the university (695). I would counter that this work is not entirely new, but that it is a tactic of the institution to silo this work into spaces where it feels new and disconnected from pre-existing networks and support structures, as a way to justify precarious conditions and under funding. It was interesting to read a piece that was focused specifically on DH within an American Studies context, but I wished for a little more broader recognition of the dynamics of other parts of the institution; I felt to an extent that many of the experiences they discussed were inherited from other parts of the institution, and real solutions could be found through broader solidarity.

I was surprised that Boyle et al’s critique did not name capitalism as the problem, and so was grateful to read the Precarity Lab’s diagnosis of “the precarity of contemporary neoliberal capitalism” at the start of their manifesto. I also appreciated their point that it is unfair to call this labor invisible when it “has always been visible in the same way that the people who do this labor have been: in plain sight but undervalued” (80). I felt that this responded to some of my criticism of Boyles et al seeing their labor as “new;” Precarity Lab recognizes that these types of labor have been invisibilized as a tactic; we’re led to believe it’s new so that we don’t realize it’s always been there, undervalued.

In contrast to Boyles et al.’s discipline-specific focus, Precarity Lab provides a high level view of other “scenes of precarity”: the Fairchild Semiconductor Plant, UberPASSPORT. I found these really interesting but felt that they zoomed too far out; again, they repeat Boyles et al’s step of not examining the academy as a whole. They have left their Humanities Collaboratory at the University of Michigan but, instead of stepping outside to analyze the dynamics of the institution, they’ve looked at the world as a whole.

I want to emphasize that I’m really not opposed to that analysis, but I wanted to read the analysis that lies between these broad and narrow perspectives. Precarity Lab notes that it’s important to situate digital platforms in historic and spatially constructed contexts to interrogate the way they’ve been positioned across time (81); what does it look like to situate these within the institution of academia and recognize how the precarity of DH mirrors the precarity of female computers in early 20th century math labs, or the precarity of visual resource curators in art departments (a weirdly siloed position often dedicated to management of visual art research collections in the latest technological format). I’m interested in an institution-level analysis as a way to articulate how the power structures of our institutes create and perpetuate precarity, and as a starting point for identifying work we can do to undo this.